W. H. Auden's Dissident Humanism

“There must always be two kinds of art: escape-art, for man needs escape as he needs food and deep sleep, and parable-art, that art which shall teach man to unlearn hatred and learn love.” - Auden

Dear friends,

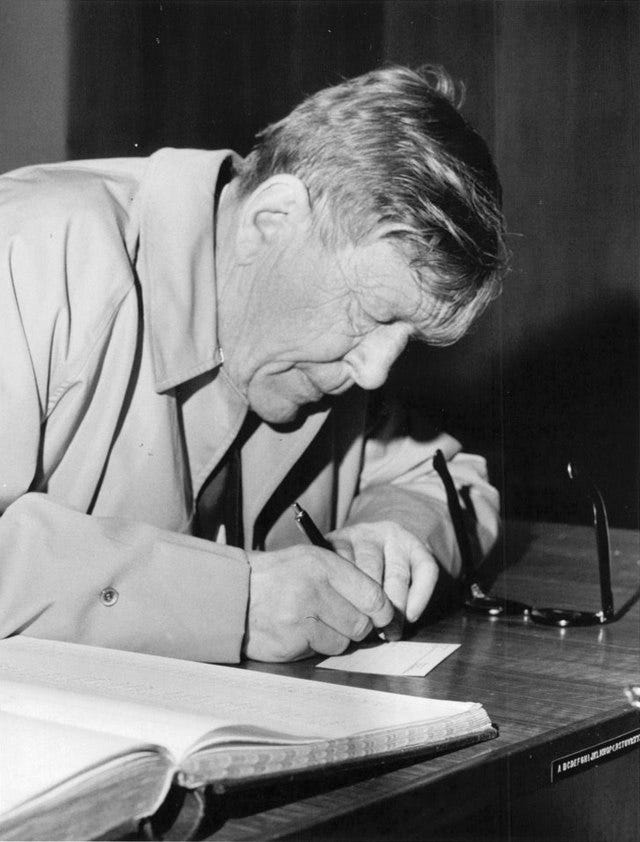

The poems of W. H. Auden (1907-1973)1 can be quite daunting. The Pulitzer Prize winner’s oeuvre is expansive,2 and his writings carry a complex and elevated air. But that’s also what makes them so much fun to analyze. I first entered college as a math major, and while the study of literature seems far removed from where I began, the overlap becomes clearer when encountering intricate and penetrating texts like those of Auden’s.3 They are something like linguistic puzzles for the heart and mind.

The Anti-Romantic Auden

Auden’s technical expertise has few equals. But, as with T. S. Eliot, his artistic prowess often creates a felt distance between the author and reader. Auden’s meticulous skill and mastery of form arguably encourage an experience that’s more intellectual than emotional. Even still, what Auden’s poems lack in warmth, they more than make up for in craft and profundity. His idiosyncratic style and incisive observations—articulating ancient truths in modern garb—make Auden a sage for our current age.

A poet’s poet, Auden showed what is possible in just about every standard verse form. As glowing as Edward Fiorelli’s commentary is, it’s also no hyperbole: “Auden is a difficult but rewarding poet. His technical skill and his enormous range and mastery of numerous poetic forms show that, though a modernist, Auden is heir to the great tradition of English poetry. He wrote sonnets, odes, epigrams, sestinas, villanelles, pastorals, ballades, satires, and a panoply of other formal types of poetry.”4

Poetic Virtuosity

Auden was especially attentive to what poetic form accomplishes. It is not simply window dressing, just a little something extra. Nor is it mere conveyance of an idea. Rather the two are bound up together. The form and content of a great poem cannot be easily separated. I won’t go as far as New Critics who say that the form of a poem is its content,5 but a master poet will skillfully employ poetic devices to shape and illuminate his insights and to guide the reader’s aesthetic and intellectual experience. There are many examples of this well-crafted integration.6

An especially excellent stand out is Auden’s “The Unknown Citizen,” a satirical take on the dehumanizing tendencies of modern life.7 Be forewarned: It’s not, on the surface, a pleasurable read. In fact, its jarring ugliness is precisely the point. Ostensibly a tribute to an unnamed subject, “The Unknown Citizen” cleverly obscures any notable details about the main character. Instead of a name, he gets an alphanumeric code: JS/07 M 378. Of him, we know only that he followed society’s norms, mechanically and unwaveringly adhering to standards set by distant bureaucrats.

His work life, home life, and leisure time were all governed by statistical averages, what a so-called “normal” person would do: putting in his time at work, participating in the community, never making a fuss. So are his daily practices and spending habits by which he contributes to the economy and embraces the modern market’s system of credit. It’s a good thing, too, because he’s being watched. The poem identifies no fewer than twelve agencies of surveillance, ranging from his union to the State’s Producers Research, the press, and his teachers. All of these reports add up to his elevation to sainthood, at least “in the modern sense of [that] old-fashioned word.”

For his part, Auden is having none of it. The punchline comes at the poem’s close, with a presumptive interlocutor asking the crucial questions: “Was he free? Was he happy?” All that is well and good, this disruptive voice protests, but what about what really matters? As we might expect, the question is irrelevant to the issue at hand, with the primary speaker calling the concern “absurd.” “Had anything been wrong,” it continues, “we should certainly have heard.”

The implication is clear. What is uniquely and positively human has been drained out by the machinations of modern existence, with the most fundamental aspects of what makes for a flourishing life—freedom, happiness—not only being irrelevant to the system but incompatible with its logic. That is the real absurdity, of course—a system that prizes people only when they are emptied of their humanity—a notion underscored by the poem’s structure.

And here is where we begin to see Auden’s genius: he manipulates the rhythm and rhyme scheme to underscore the troubled nature of a society bereft of humanity. Despite surface appearances, such a life is ultimately off balance. What begins as a regular ABAB rhyming pattern falls off by line 6. Like a car misfiring, the rhymes jut out in quick succession, packed in too close with “retired,” “fired,” “views,” “dues,” “plan,” and “man” following line after line. As Carol Lawson Pippin articulates, “The reader can never get his footing. What we’re left with instead is disorientation.”8

Hopeful Hints

Auden’s embrace of Christianity in 1940, after an extended period wrestling with its tenets, practices, and implications, unsurprisingly changed the tenor of his poetry. We can see this shift, ironically enough, in his a-theistic—and masterful—ekphrastic verse, “The Shield of Achilles.”

Taking Book 18 of The Iliad as inspiration, Auden modernizes the shield Hephaestus carved for Achilles, juxtaposing the classic tale of heroism and virtue with industrialized society, drained of individuality and character:

An unintelligible multitude,

A million eyes, a million boots in line,

Without expression, waiting for a sign.

There is no Achilles on the horizon, no Hector to overcome. Just a mass of men, reduced to automatons. And Hephaestus is no Christ, no personal god who cares about his creatures. He’s more akin to the surveillance state of “The Unknown Citizen,” seeing no difference between the figures on his shield.

Unlike this anonymous subject, however, the figures in this poem endure great suffering and are in dire need of rescue:

A ragged urchin, aimless and alone,

Loitered about that vacancy; a bird

Flew up to safety from his well-aimed stone:

That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third,

Were axioms to him, who'd never heard

Of any world where promises were kept,

Or one could weep because another wept.

Hephaestus remains unmoved, but the reader cannot be so dispassionate. We ourselves are implicated in the scene depicted. We recognize the inhumanity displayed, even if it is extreme. And we resist—or should resist—succumbing to such a fate. It is by the lack of empathy, the lack of hope that “The Shield of Achilles” speaks so powerfully to the need for both.

Poetry as Witness

How does one begin to rehumanize such a world? We would be justified to think Auden would champion poetry as the answer. But that’s not quite right. Such an attitude is too imperialistic and bombastic for him. Early in life Auden may have bought into something like Percy Bysshe Shelley’s overblown pronouncement that “[p]oets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” But, as Alan Jacobs explains, Auden’s religious conversion tempered such hubris.9 He landed instead on the notion that “poetry [is] valuable only when it acknowledged its hopeless, incompetent distance from anything true or good that it tried to represent.”

We see something of this idea in Auden’s perennially baffling line from his tribute to W. B. Yeats: “[P]oetry makes nothing happen.” Rather, it survives, he says, in human life, in everyday and unexpected experiences (“where executives / Would never want to tamper, flows on south / From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs, / Raw towns that we believe and die in”). Poetry’s value is derivative, he seems to suggest, absolutely dependent on the people who write it, the ones who read it, and most significantly on the deep truths toward which it gestures.

On Jacobs’ understanding, “Auden uses poetry to remind us of what poetry can never give us. But, in the end, this assigns poetry a genuine and important role, as it points always beyond itself in a strangely mute witness to that of which it is unable definitively to speak.” Poetry, then, is something of a reminder of what we already intuitively know. The poet, we might say, is treasure hunter and jeweler combined—locating, unearthing, and preparing gems, invaluable nuggets that they help us reclaim.

“Musée des Beaux Arts” is a vivid example of this Auden distinctive. Here, Auden poetically renders Breughel’s depiction of the fall of Icarus, underscoring how little impact such a personal catastrophe would have on others. Auden is telling us nothing new. We have all experienced how tragedy happens alongside the mundane. But what Auden does, in this scene and elsewhere, is remind us of what matters.

It is this very poem—and others like it—that gives us pause in the everyday activity of life. It calls us to stop, to pay attention. And in the process, we just might recover a bit of our humanity.

Miscellany

Recently I discovered Devin Kelly’s Ordinary Plots newsletter. Each week, Kelly covers a poem and provides insightful analysis and beautifully vulnerable and personal reflections (see his take on Chet'la Sebree's "Oceans could separate us, but no" for example). I appreciate these especially because they’re often poems (and poets) I’m not familiar with, so I relish both Kelly’s recommendations and wise guidance in how to navigate the material. Highly recommended.

Also recommended is Shadowlands Dispatch, an outreach of the Society for Women of Letters. Their site encompasses a wide range of content, including original articles, reviews, and study guides, all from an overtly Christian stance. Readers of Divine Echoes will especially appreciate their monthly poetry column, Poetica, where they introduce subscribers to working poets. Check out this one on Bradford Winters, which includes his poem “Farther, Father, Feather.”

Until next time, my friends, I’m wishing you all well.

Marybeth

For more on the work of W(ystan) H(ugh) Auden, including examples of his poetry, see Poetry Foundation’s overview at this link: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/w-h-auden

Best known for his poetry, Auden also wrote drama, libretto, and nonfiction. He also translated and edited a number of classic texts. All told, he published over 30 books and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his 1948 Age of Anxiety.

See Sarah Hart’s 2023 New York Times article exploring these links: “The Wondrous Connections between Mathematics and Literature.” Hart has a book along these lines as well: Once Upon a Prime.

Edward Fiorelli, “W. H. Auden,” Cyclopedia of World Authors, 4th revised ed., Jan. 2003, 1.

I do, however, appreciate the call back to the text and the challenge of close reading that New Critics pushed for. See this link for some background on that movement: https://owlcation.com/humanities/what-is-new-criticism.

I won’t even list examples here because to do so might suggest these are exceptions rather than rule in the poetic field, which at its best should always aim at this integration. I will just mention Cleanth Brooks’ The Well Wrought Urn, which examines 10 poems as paradigms of that signature poetic structure.

Carol Pippin connects the title to the heroic “unknown soldier,” recognized because he died in defense of the society for which he fought. So, too, with Auden’s titular character, albeit it’s a metaphorical death. See Carol Pippin, “The Unknown Citizen,” Masterplots II: Poetry, revised ed., Jan. 2002, 1.

Carol Lawson Pippen, “The Unknown Citizen,” Masterplots II: Poetry, revised edition Jan. 2002, pp. 1-3, 3.

See Alan Jacobs’ discussion on this point here: “Auden and the Limits of Poetry.” This article from First Things is also worthwhile for Jacobs’ wrestling with the contradiction between Auden’s professed Christian faith and his lifelong romantic partnership with Chester Kallman.