Dear friends,

I started this newsletter on the conviction that we must carve out space to recognize and honor the good, true, and beautiful. Something in us knows we are not machines to be used up. On Christian theology, we are divine image bearers meant for communion with our creator, instilled with the desire to better know him and his world, and charged with loving and serving our fellow image bearers.

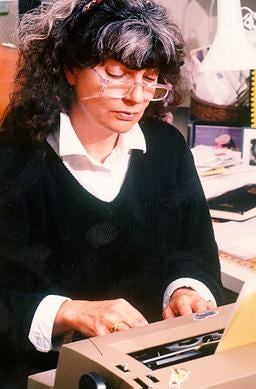

Poetry at its best can awaken us to these truths and reinforce our commitment to them in the face of day-to-day demands and urgencies that threaten to displace them. That’s what we find in the work of Jane Kenyon (1947-1995),1 a poet for whom my admiration grows with every encounter.

Kenyon’s Uncompromising Hope

Kenyon, more than most, understood the existential power of poetry to put us in touch with fundamental realities, especially when the temporal and ephemeral obscure our vision. Even before her untimely death of leukemia at age 47, Kenyon struggled with the “all but unendurable” anguish of chronic depression.2 Despite that struggle—or (counterintuitively) because of it—Kenyon’s poetry bears the marks of hope, a hope that’s all the more compelling for having faced down and overcome real suffering through a tenacious and active faith.3

Kenyon was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and was raised in a rural area outside town. She attended the University of Michigan where she met her future husband, poet and professor Donald Hall. The two married not long after her graduation and moved to New Hampshire in 1975, settling down in a farm that had been in the Hall family for generations. The New England countryside and the Christian faith she found there became defining features of her career.

Kenyon encountered Christianity in her childhood by way of her grandmother but rejected it as fearful and domineering. What she discovered in South Danbury Christian Church as an adult was instead numinous and richly aesthetic, which resonated with her artistic sensibilities. Minister Jack Jensen often quoted poetry in his sermons, and recommended she read the work of early Christian mystics such as Julian of Norwich and St. Therese. Kenyon was hooked. She embraced Christian faith personally and poetically, giving her life and work a strong theological grounding and purpose.

A Poetry of Thresholds

The mark of Kenyon’s faith on her poetry is simultaneously pervasive and subtle. Her attentiveness to nature is but one feature of that connection. Because much of Kenyon’s life was spent in rural areas, it’s unsurprising that nature would loom so large in her verse. But its function extends beyond pure imagery. Like Keats, Kenyon sees in nature’s cycles—of seasons, of days, of months, of years—patterns by which we map our lives and understand ourselves, both individually and collectively.

Her lyrical “Let Evening Come” at once proclaims and embodies this theme. As the poem begins, it’s late afternoon, with the sun on the verge of setting. In its incessant rhythm and repetition, the poem moves readers relentlessly toward close of day. And animal, setting, and person alike give in to that next phase:

Let the cricket take up chafing

as a woman takes up her needles

and her yarn. Let evening come.Let dew collect on the hoe abandoned

in long grass. Let the stars appear

and the moon disclose her silver horn.

Notice that the speaker is not advocating resignation, as though the evening that awaits us signifies sheer loss. Rather, the tone—conveyed by the poem’s lush language and imagery—is inviting, inspiring, enchanting. Such a posture is possible, the speaker believes, because a benevolent governor lies behind the cycles—of our days, of our lives, and of existence itself. It’s an anti-quietism, in fact, that closes the poem. The speaker encourages a change of heart and mind. The final lines enact a paradigm shift that invites us to rest in transcendent peace:

Let it come, as it will, and don’t

be afraid. God does not leave us

comfortless, so let evening come.

To believe in a divine lover beyond material endings, beyond death, demands something of us, a trust that doesn’t come without effort. But with the right slant of light, with the beautiful framing Kenyon’s poems offer, we see that such belief is not only possible in this vale of tears but appropriate. Joy and sorrow might well be irrevocably intertwined in this world, Kenyon’s poems affirm, but even more insistently, they testify that a grace received will tip the scales to God’s inexhaustible love. This is the vision that critic Carol Muske refers to when she says that Kenyon “sees this world as a kind of threshold through which we enter God’s wonder.”

The Luminous Particular

For Kenyon, there is but a thin membrane separating the external world of images and the inner world of experience and emotions, for the poet and reader. The poet’s job is to exploit that connection, drilling down to specific scenes and objects that unlock for readers an inner world and illuminate truth that goes beyond the senses. This poetic quality is what Kenyon herself called “the luminous particular,” a phrase she coined while translating the work of Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

John H. Timmerman explains it this way: “The reader enters and owns it [the poetic object], rather than the poet simply declaring. The poem thus requires absolute honesty and exacting care by the poet.”4 In the case of “Reading Aloud to My Father”, Kenyon’s speaker zeroes in on a precise scene—an adult child selecting a book to read to a dying parent.

The book is Nabokov’s memoir, Speak, Memory, and the opening line becomes for speaker and father a touchstone, a means of looking back and looking ahead:

I chose the book haphazard

from the shelf, but with Nabokov’s first

sentence I knew it wasn’t the thing

to read to a dying man:

The cradle rocks above an abys, it began,

and common sense tells us that our existence

is but a brief crack of light

between two eternities of darkness.

That moment, when the child reads for her parent, merges with Nabokov’s revelry—inducing reflections on birth, death, human existence. It is an individual moment yes, but one tied inextricably to a thousand, thousand moments, an untold number of details that all meet in that scene:

The words disturbed both of us immediately,

and I stopped. With music it was the same—

Chopin’s piano concerto—he asked me

to turn it off. He ceased eating, and drank

little, while the tumors briskly appropriated

what was left of him.

And from that instance, comingled with memory, is born a pronouncement, an insight into the human condition. As the poem closes, the particular scene expands out. Yes, we walk our own unique paths in this life, but those paths are littered with the same signs, the same landmarks, the same outposts. The dying parent and the mourning child remain distinctly individual yet accrue universal application:

At the end they don’t want their hands

to be under the covers, and if you should put

your hand on theirs in a tentative gesture

of solidarity, they’ll pull the hand free;

and you must honor that desire,

and let them pull it free.

Through this scene, Kenyon has dredged up her own pain and sorrow, in having lost her own father, to poetically wrest from it hard-won insight, all for the benefit of her readers.

Pursuing the Great Goodness

The most pressing questions of Kenyon’s work involve suffering and the presence and power of God. These were live questions for the poet, as Timmerman explains. When Kenyon wonders, “Can God lead me through this? Or, even, is there any meaningful presence of God at all?” the need for answers was real, “as the twin demons of bipolar disorder and leukemia began raking their scaly claws inside her.”5

The dynamic interchange of suffering and wonder comes into full view in Kenyon’s stunning poem, “Happiness.” In the opening lines, we hear echoes of the parable of the prodigal son’s return:

There’s just no accounting for happiness,

or the way it turns up like a prodigal

who comes back to the dust at your feet

having squandered a fortune far away.

There’s good news for the long-lost son, but what of the ones abandoned? Kenyon’s poem shifts the focus to the family who welcomes the wayward home. They, too, are caught up in celebration, all the more intense perhaps because it comes from loss restored:

And how can you not forgive?

You make a feast in honor of what

was lost, and take from its place the finest

garment, which you saved for an occasion

you could not imagine, and you weep night and day

to know that you were not abandoned,

that happiness saved its most extreme form

for you alone.

And in a brilliant twist, happiness opens up to its most prodigal form, bestowing its wares on any and all comers, worthy by the world’s standards or not:

It comes to the monk in his cell.

It comes to the woman sweeping the street

with a birch broom, to the child

whose mother has passed out from drink.

It comes to the lover, to the dog chewing

a sock, to the pusher, to the basketmaker,

and to the clerk stacking cans of carrots

in the night.It even comes to the boulder

in the perpetual shade of pine barrens,

to rain falling on the open sea,

to the wineglass, weary of holding wine.

This is Kenyon’s vision of the world, one she hopes her readers will embrace, even and especially amid suffering and sorrow. Timmerman argues that for the poet, “faith was the means by which one lived through such experiences.... [Faith] is active, pursuing the presence of God in a world rent by suffering.”6 And it is this faith that animates Kenyon’s verse, testifying to the great goodness and offering us a doorway to experience him ourselves.

Miscellany

A Man for All Seasons (1966) has been on my to-watch list for an embarrassingly long time. Everything I’d heard about it made it seem like the exact kind of film that would resonate with me: a moral exemplar standing on conscience against abuse of power; consideration of a significant era in church and state history; rhetorically powerful lines delivered with dramatic flair; and an uncanny if not eerie resemblance to our contemporary cultural and political moment.

This weekend I finally made time for the movie, and I was not disappointed. Honestly, the whole thing was worth it for this exchange between More and his eventual son-in-law William Roper

Roper: “So, now you give the Devil the benefit of law!”

More: “Yes! What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?”

Roper: “Yes, I'd cut down every law in England to do that!”

More: “Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned 'round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws, from coast to coast, Man's laws, not God's! And if you cut them down, and you're just the man to do it, do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I'd give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety's sake!”

I’ll leave you with the scene in full, and I look forward to talking with you again next week. - Marybeth

For more about Kenyon, see Poetry Foundation’s overview, which includes links to many of her poems: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/jane-kenyon

Kenyon regularly discussed her bouts of depression and their influence on her writing. You can see some of that discussion (including the quote referenced above) in the documentary Bill Moyer created about her marriage and creative partnership with poet Donald Hall, A Life Together. Find the transcript here: https://billmoyers.com/api/ajax/?template=ajax-transcript&post=423

Joshua Wolf Shenk, interestingly enough, makes a similar point about Abraham Lincoln’s struggle with depression. Far from being a political liability, Shenk argues, Lincoln’s lifelong bouts with depression fortified his moral character and equipped him to lead the nation through the Civil War. “Lincoln’s Great Depression,” Atlantic, October 2005. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2005/10/lincolns-great-depression/304247/

John H. Timmerman, “In Search of the Great Goodness: The Poetry of Jane Kenyon,” Reformed Journal, May 16, 2003, https://reformedjournal.com/in-search-of-the-great-goodness-the-poetry-of-jane-kenyon/.

Excellent commentary! I really enjoy how you introduce poets to me that I may not have encountered before. Thank you for your insights and the movie clip, too!