For the Love of the Bard

"Shakespeare was the Homer, or Father of our Dramatic Poets" - John Dryden

Dear friends,

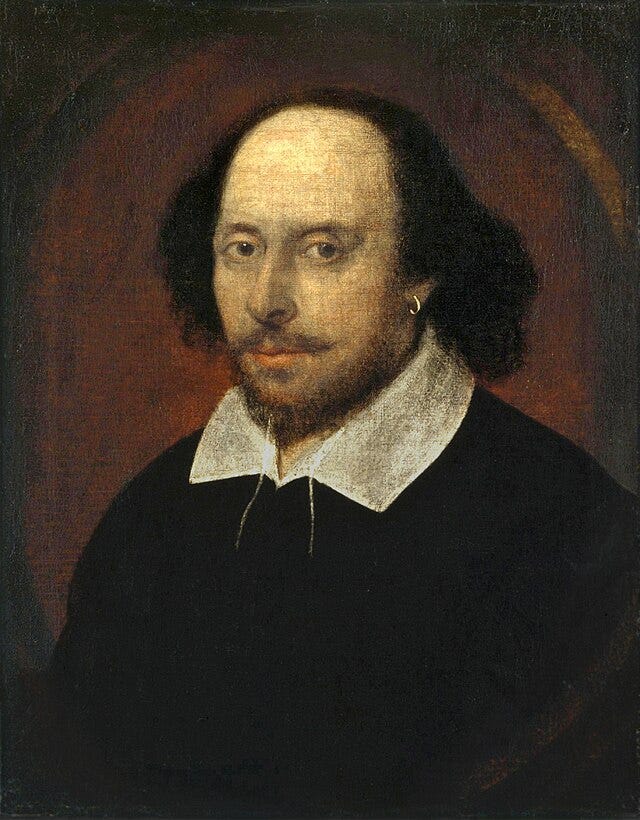

I anticipate that the subject of today’s newsletter will provoke strong reactions—for good or ill. Hardly anyone is neutral on William Shakespeare (1564-1616). He’s been championed in theatrical, literary, and educational circles for centuries, and that trend doesn’t appear to be abating anytime soon.1 Even still, Shakespeare’s language and themes are often challenging, and compulsory reading of his plays in high school may make many (rightly or wrongly) resistant to revisiting his works after graduation.

But whether you adore Shakespeare or abhor him,2 I hope you’ll give this post a chance. I don’t presume to offer a comprehensive introduction to his work or to defend his cultural dominance. Rather, I want to showcase how enjoyment, understanding, and appreciation of this luminary of English literature intertwine and can mutually reinforce one another.

Surprised by Shakespeare

In November of last year, Shakespeare’s work filled up our social media feeds in a rare viral moment for the bard. You may remember seeing clips of Judi Dench reciting one of his sonnets on BBC’s Graham Norton show. That video captivated so many because it presented Shakespeare to us anew. It brought this supposedly staid and archaic figure back to life, as it were. (Well, Dench’s command performance also played a part.)

You can watch (or re-watch) here:

Performance as Interpretation

After a bit of banter, Norton asks Dench about Shakespeare’s influence on her life and work. Dench—a renowned actor of film, television, and stage—has performed in no less than 37 productions of Shakespeare’s works, and her affinity for the playwright is well documented.3

“We quote Shakespeare all the time,” she tells Norton, and for good reason. The poet playwright articulates the stuff of our humanity, giving shape to our hopes and fears, frustrations and joys, our victories and defeats. Shakespeare shows us at our best and worst, and everything in between.

As Dench further explains, “You only have to go to those plays and be in any kind of those situations—being in love or being jealous or being angry or being whatever—and you will find that there is a way of him summing up that is completely sufficient for what your emotion is.”

Then, in a moving and unexpected transformation, she demonstrates how that’s so. She shows more than tells. The lighthearted repartee between host and guest gives way to the sonnet’s somber monologue. The laughter is hushed, and we along with Norton and others find ourselves caught up in the drama latent in Shakespeare’s words and manifest in Dench’s delivery. Even Arnold Schwarzenegger was impressed.

In Dench’s refrains, we both hear and feel the speaker’s despair, her loneliness and jealousy:

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself and curse my fate,

Dench has thrown herself fully into this role, and she pulls us in along with her. What Poetry Foundation describes of Shakespeare’s sonnets, Dench’s recitation embodies:

Drama is conjured within individual poems, as the speaker wrestles with some problem or situation; it is generated by the juxtaposition of poems, with instant switches of tone, mood, and style; it is implied by cross-references and interrelationships within the sequence as a whole.

When Dench shifts from anguish to hope in the sonnet’s last quatrain, her voice and demeanor brighten as well, tracking the trajectory of the poem itself:

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

(Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven’s gate;

The words on the page map out the path that Dench’s presentation travels. It’s one thing to cognitively recognize the alliteration replete in these lines, for example, but to hear Dench melodically voice “like to the lark” and “hymns at heaven’s gate” is to become attuned to emotion animating writer and speaker alike.

Shakespeare’s Big Tent

For his part, Shakespeare’s “large and comprehensive soul,” as John Dryden described it, is expansive enough to accommodate any and all comers to his writings. While his work is of the Renaissance, emanating from that period’s fertile cultural dynamics, its relevance is in no way limited to that time or place. Nor is it applicable to only a certain segment of the population.

African American author Maya Angelou, for example, found in Shakespeare a voice for the oppressed. Namely, in Sonnet 29 (the same one Dench recites), she discovered words that spoke precisely of her experience as a Black girl from Stamps, Arkansas. As a child, Angelou was an avid reader, devouring all the volumes in her town’s library, including the complete works of Shakespeare. She admits later that although she didn’t initially understand his writing that much, she nevertheless loved it.

Angelou could sense within it a visceral connection, conjured by the sounds, rhythms, and atmosphere of the work. It was that love, those humanistic ties that bind, that kept drawing Angelou back again and again to Shakespeare’s plays and poems. With every revisitation would come deeper understanding. Seeing Shakespeare through Angelou’s eyes and hearing how powerfully his poetry speaks to her can awaken in us that same sense.

Shakespeare Through Another’s Eyes

Such is the nature of the symbiotic relationship Shakespeare has with those who perform his works. By returning to the Shakespearean well and drawing out fresh inspiration, performers keep his legacy alive and interpret it for the current moment. They thus serve both him and us.

It’s something I had the privilege to experience often at the American Shakespeare Center (ASC) and Blackfriar’s Playhouse in Staunton, Virginia (a hard loss when we moved Texas). Through lively and updated performances, the cast, like Dench, is able to cut down barriers to Shakespeare’s work and invite us to experience what he has to offer. (Side note: if you live anywhere close to Staunton, a trip to the Shakespeare Center is well-worth the effort. Maybe make a weekend of it!)

It’s a gift to see Shakespeare through the eyes of someone who understands and appreciates his work. David and I had such a friend in Mark Foreman. Mark was a local legend in Lynchburg’s theater community, and his love of Shakespeare was infectious. Besides performing in multiple Shakespeare productions, Mark participated in the work of the Staunton Shakespeare Center through regular attendance at their plays, workshops, and conferences. But he was not content merely to enjoy the plays himself: he shared that love with others through organized trips to the playhouse and by talking him up among family and friends.4

There’s an interesting overlap here, between Mark commending Shakespeare to us and the punchline of Sonnet 29. Shakespeare’s speaker, having lamented all the ways he feels deficient in comparison with others’ strengths, ultimately realizes that it’s in being understood, loved, and appreciated that true success lies: “For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings / That then I scorn to change my state with kings.”

If that’s the case, we need only to canvass Shakespeare’s manifold and proliferating adaptations, recitations, and productions to know that the poet and playwright was rich indeed.

Miscellany

I’ve written about Shakespeare’s sonnets before, and I confess that I was tempted to give myself a bit of a break this week and simply reprint that here. But I resisted since my goal with this newsletter is to implement and sustain a regular writing schedule. Even still, you may find that earlier post of interest.

Here’s a bit of it:

Shakespeare’s name is nearly synonymous with literature, both because of the volume of creative works he produced and the thematic and stylistic intricacies of those works. The great Neoclassicist John Dryden, in recognizing Shakespeare’s genius, suggested that his lack of formal training in writing underscored his greatness since, despite that, he excelled at elevating any given subject matter. In so doing, Dryden argued, he towered over even the greatest of Renaissance playwrights, having “the largest and most comprehensive soul” with a remarkable ability to draw audiences in emotionally. Shakespeare made them feel the force of his stories, not merely watch the plot play out.

Yet before Shakespeare made his name as playwright, he produced poetry, lots and lots of poetry. In fact, it is in his poetry that Shakespeare’s literary (and social) aspirations are most clearly revealed. In the last decade of the 16th century, when the theaters were closed to prevent the spread of the plague, Shakespeare explored other avenues for making a living....

Given that Shakespeare has left little personal historical record, particularly in light of his outsized influence on the literary world, it’s understandable that the details of his poems would evoke speculation: just who is the “dark lady” of sonnets 127-152; and who is this “young man” named in the first 126? What do these poems, and especially their subjects, tell us of Shakespeare’s loves and losses, his desires and struggles? Although there’s little outside historical record to confirm or disprove interpretive conclusions on these scores, the conjecture is almost too delectable to pass up. Often overlooked in such critical studies, however, is much concern with the aesthetic and thematic qualities of the poems themselves. And that’s a shame because the combination of Shakespeare’s linguistic dexterity and his emotional insights with the precise and well-structured sonnet form make such an examination eminently worthwhile....

The rest of the piece considers how Shakespeare customized the traditional sonnet form popularized by Petrarch in Italy several centuries earlier. (Shakespeare shifted from an octave/sestet structure to three quatrains with a concluding couplet.) And it closes by examining three specific poems as instances of his unique approach: Sonnets 130 (“My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun”), 73 (“That time of year thou mayst in me behold”), and 55 (“Not marble nor the gilded monuments”).

I hope you all have a great week and are able to fit a little poetry in. If you’re up for some Shakespeare, I recommend Kenneth Branagh’s 1993 Much Ado About Nothing.

Take care all,

Marybeth

Even with the contemporary bent in literary studies toward critical theory, Shakespeare studies remain popular (even if they now often assume an ideological flavor). See this article by Harvard professor Jeffrey R. Wilson for analysis of how Shakespeare’s reputation has fared through the years.

Admittedly, I chose this exaggerated pairing for rhetorical effect (and am very proud of the assonance, rhythm, and rhyme of it). Most of us are somewhere else along the spectrum when it comes to Shakespeare.

See Dench’s performances catalogued here. She also has a book about Shakespeare, The Man Who Pays the Rent. It’s a collection of conversations about the playwright between Dench and fellow actor, Brendan O’Hea.

You can read David’s tribute to Mark at this link. Mark’s daughter, Erin, followed his footsteps into theater and acknowledges her debt to him here. Mark’s friend, Sally Southall, also recognizes his support of her work and education in her dedication to her MFA thesis.